#BringBackTheNatureTable

- Feb 16, 2020

- 6 min read

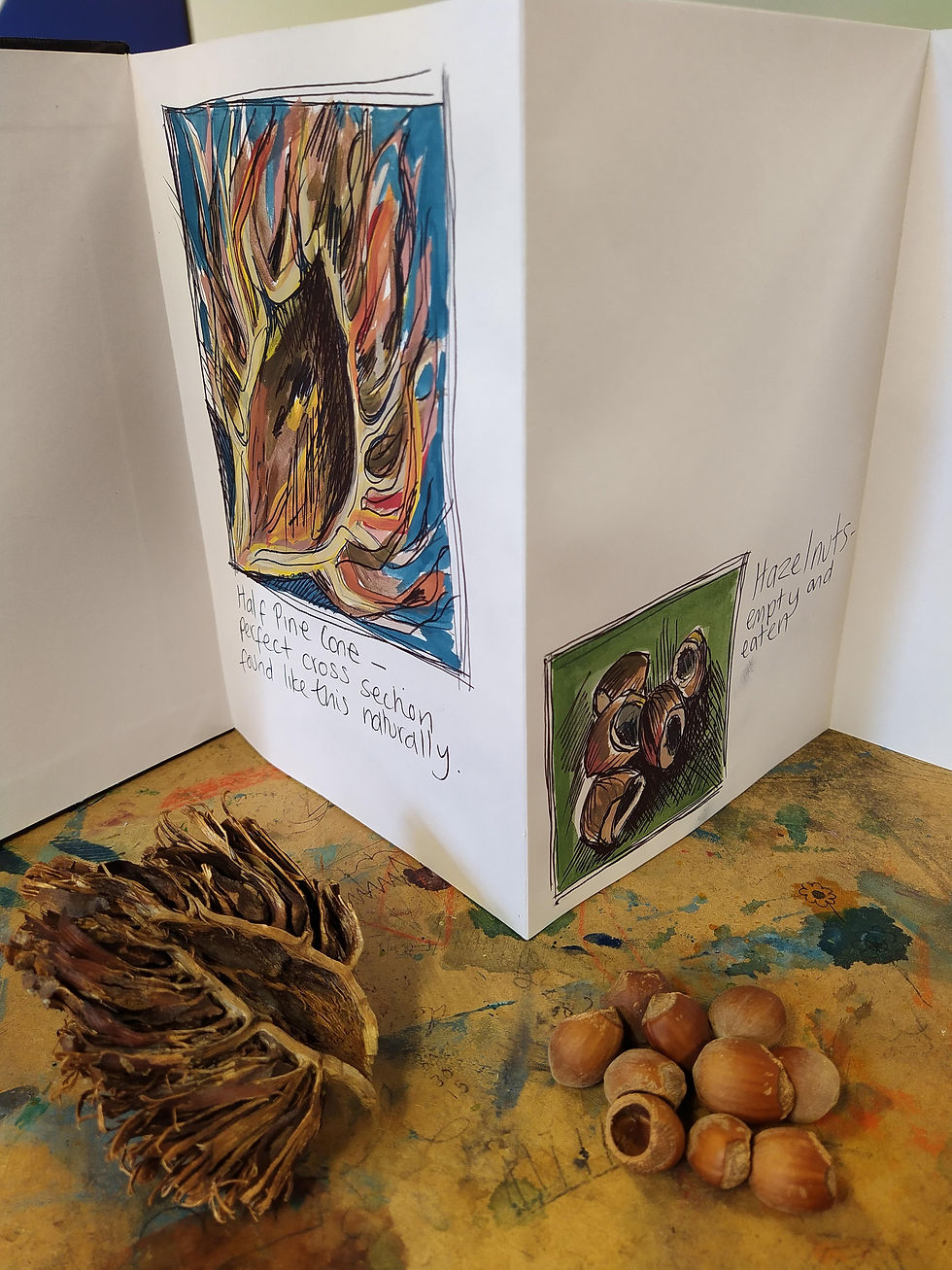

Do you collect stuff when you are out on walks? Do you end up with pockets full of nature- feathers, conkers, a red autumn leaf, a twig with a nice bit of lichen growing on it, shells, mermaids’ purses, a special stone? I do and so do the rest of my family. My eldest daughter has a collection of shells on the dash board of her first car. Our house has areas that seem to attract the collection of bits of nature that we find out and about. I have a jar of hazelnut shells eaten by mice and another larger jar full of pinecones half eaten by squirrels. We also have our fair share of dead stuff, skulls, bones and animal vertebrae. It's not unusual for us collect and then later find the same objects in various states of decomposition We are no stangers to the cabinet of curiosities or the wunderkammer as these intriguing and sometimes disturbing collections are sometimes called.

I believe the instinct to collect nature comes from an inherent curiosity, a desire to learn, to understand, to observe. This can later extend into a natural desire to categorise to classify. To do this, a person must compare, contrast. I am not a scientist, I am more of an artist but I understand these collecting behaviours as being the beginnings of a very sensory, experiential approach to developing crucial scientific and artistic skills. Historically, explorer journals were full of drawings and observations of the natural world, many naturalists descibe childhoods with collections of all kinds of dead, smelly, creatures, plants or other items-the beginning of science and art is sensory.

Above is the work of Coneptual Artist Mark Dion, the place where art, science and natural history overlap and a huge influence on my work, on paper and in my outdoor practice.

Many people of a similar age, will remember with much fondness, their school nature table. A place for the nature finds of children on their walk to school or their family trip out, it was a simple and basic way to teach- without teaching. The nature table would teach us what grew and lived locally, how nature changed through out the seasons, with the occasional more exotic find from a child’s family holiday abroad, that would teach us about more global flora and fauna, a shell from an African land snail or a volcanic rock for example.

The nature table certainly had a massive impact on me as a child and me as an adult. It influenced the work I did as an artist for several years titled Miss Elvy’s Cabinet of Curiosities. It continues to inspire my art and my teaching now. I never fail to experience the wonder of a natural treasure found while out and about or even better, found by a child who brings it to you to ask what it is. I am fascinated by natural collections, equally excited by museum-based collections and the nature find contents of kids pockets. Recently this work has been coming back to me but for different reasons. My research and practice have a focus on inclusion in outdoor learning opportunities for people experiencing poverty. I have in past blogs discussed the idea that the outdoors can be a privilege and I have a growing understanding of the barriers to getting out into nature that many people may experience when living in poverty. What if nature tables went some way to tackling the sometimes-unavoidable inequality inherent in outdoor learning?

I grew up in poverty and I am sure that the nature table gave me access to the wonder of the natural world even if I would never see some of these objects in their natural context. It also made me want to contribute to it and so where I could not contribute in other ways in the classroom when children were invited to share particular items from home, I could guarantee that I could pick up a leaf or a dandelion clock on the way to school and feel I had something to offer. It made me alert to what was growing or falling from trees even if limited to my tiny environmental bubble. I remember a kid bringing in a dead stag beetle in a match box one day. I had never seen such a thing! More than the dead specimen in the match box though, what really mattered most about this nature table encounter, was that I later knew what the beetle was, when one crossed my path on my home one day after school.

Take it from me, the nature table is a great environmental equaliser. A simple addition to any classroom, easy to set up. When working as the outdoor lead at a primary school I was given a display area that had some shelves. The shelves became our nature table. It was in the corridor, anyone could see it. Kids would bring stuff, staff would offer their finds too. We would add whatever we could find in and around school, sweet chestnuts, enormous pine cones, hedgehog fungi. We put things in jars for fun, like a kid’s museum, to preserve them or just to keep the pebbles shiny. It was not always tidy and admittedly the tolerance and patience of the teaching staff, cleaners and the head, was much appreciated.

It is the unifying and equalising quality of the nature table that intrigues me the most at the moment. I was pleased to find someone who felt the same;

“Some days it smelt of decay (crab claw, leaf mould, bearded venerable marrow) and some days it smelt of life (hyacinth, tadpole, apple). It shared with you the treasures and the mysteries of the world, the faintly disgusting and the sweetly uplifting, and it knew how to surprise and hook you with its burrs, and reward you with its fronds and surprises.”

The writing and work of Dr. Matthew McFall or AKA the agent of wonder, explores the treasures of the nature table in the context of poverty and education. A government study from 2016 pointed out “clear social inequalities in how children are accessing natural environments” and “a correlation between the frequency at which children visit the natural environment and both their ethnicity and socio-economic status.”

In the book, The Working Class- Poverty, Education and alternative voices, Ian Gilbert asks:

“What can the lowly nature table do in order to help us address the inequalities that are the focus of this book? What is clear is that, at the risk of missing my classroom fixtures and fittings, this school feature is a table that opens a door and can set an individual on a lifelong path in which the natural world and all its benefits will feature strongly”

Yes! That’s me!

And I am sure many, many others.

Join me then, in the campaign to bring back the nature table. For all children, but particularly for those who may have a limited access to getting outdoors and into nature. Understand that this nature knowledge and nature confidence is significant cultural capital, that some will never gain otherwise. Understand that naturalists, explorers, adventurers, artists, environmentalists and nature writers are often from privileged backgrounds or have had the benefit of a private education, they will have the benefit of massive cultural capital. I am not suggesting that all inequality in outdoor learning can be solved with just a nature table, there are of course many barriers for families and children who experience poverty, but this one single addition to your nursery, classroom, front room, kitchen window sill or car dash board can make a massive difference. Let it be led by the children. If you are the teacher/leader/parent, contribute to it as an equal, as another collector, fellow explorer and do not take it over for your own purposes, no matter how well intentioned. A nature table is not the same as a beautifully planned and adult cultivated display about flowers or tadpoles for example. Let it be messy, let it be smelly and become rank, it's all part of the learning. A nature table is a place where all finds are welcome and loved and studied in all of their ”yuk and wow” glory as Mc Fall would say.

Join in by taking photos of your nature table and posting for all to be inspired.

Comments